How do you write about loneliness?

By Daniël Rovers

1.

I have always been good at ‘being alone’, at least that’s what my mother has always claimed, but with a sense of satisfaction in her voice – the feeling that she had succeeded as a parent because her child was able to enjoy himself and not constantly crave attention, was not constantly looking for new stimuli, but was satisfied with a game he made up himself and the books that were available to him.

An idyllic picture, but is it correct? Was I really that happy and independent as a child, or was I often alone and simply made the most of it?

We should remember that: who we were before we were saddled with a ‘personality’.

The past used to seem much closer, as if you could return to it at any time, disappear into it like into the tall row of conifers in the neighbour’s garden, with that dense greenery you could lean against, until you fell through the phalanx of bushes, right onto a strange lawn.

As a child I was much more nostalgic than now. While everything was constantly changing, every month, I always wanted to go back to who I had been a while before.

One of those memories that seems to have barely faded over the past 25 years and has since solidified into an anecdote: I’m ten years old, lying at home in the hallway next to the doormat, feeling lazy and dull, and can’t decide whether that is nice or annoying. There is a visitor, and from the living room I hear my mother say something, she calls my name and comments on my behaviour. She says that I’m always so good at entertaining myself when I’m alone, that I never seem to get bored.

I turned 11 and I turned 12, and the emptiness started to spread over the days, like a huge grey cloud, especially on Sundays, when there was never anything to do in the street; for one reason or another people preferred to stay indoors, perhaps because they had learned to do so in the past.

In our house, it was freezing cold in all the rooms in the winter except in the living room, where the four of us were locked up on those long Sundays, my sister on her side of the Formica dining table with a square tin of coloured pencils open on the dark yellow tablecloth. If you squinted at it from a couple metres away, that box of pencils looked like a beautiful sunset.

We had a reproduction of Meindert Hobbema’s The Avenue at Middelharnis hanging above the blanket chest in the living room; the Dutch poplars in the painting were reminiscent of tropical palm trees. There was a Meindert Hobbemastraat in our town, but that’s not where we lived.

In the street where I lived, there were trees whose leaves turned as yellow as paprika crisps in the autumn. Sometimes it rained, sometimes it stormed, and at that time it still snowed occasionally, but on most days it was grey outside and one could not even detect any movement in the sky.

At first my sister would just draw lines on the white paper, she could easily spend an entire afternoon doing that. She carefully copied all the animals from a thick book full of animal prints, a book she had borrowed from the library. When asked if she wanted to become an animal trainer when she grew up, she just shrugged her shoulders and continued.

‘Just look at what your sister can do!’ my mother called me in when my sister showed the results of a weekend’s worth of drawing. She was right, it was all done very well, yet I never felt a twinge of admiration or jealousy; instead I was relieved that I wasn’t the draftsman who had to make all those thousands of pencil marks to produce such a drawing.

The room remained silent, with nothing to hear but the abnormally loud ticking of the grandfather clock and the creaking of the table when my sister drew a heavy pencil line across the paper. The long hand of the clock moved so slowly down and then up again that it seemed time and again as if it had come to a permanent stop in a time vacuum that you could get sucked into at any moment.

Imagine you are staring at a bathtub that you know is draining, but the tub is so huge that all you hear is a muffled chugging and gurgling from the drain. There is hardly any movement in the water, and all you can do is wait. You have nothing to do, while the water slowly cools and wrinkles appear on your fingers, a harbinger of the old age to come.

Loneliness also has to do with a lack of words, and thus a lack of the knowledge necessary to have any sort of perspective on the world. What you lack is the ability to experience silence not primarily as a threat, but as a distance that will offer unexpected possibilities.

Those long empty Sundays of the past, I cannot describe them well and I would prefer not to do so. If I succeeded, I would again attain that same insignificance that once had me in its clutches for days on end.

That anxiety from those times returns when I think about them, again putting me in danger of being locked up here in my own thoughts.

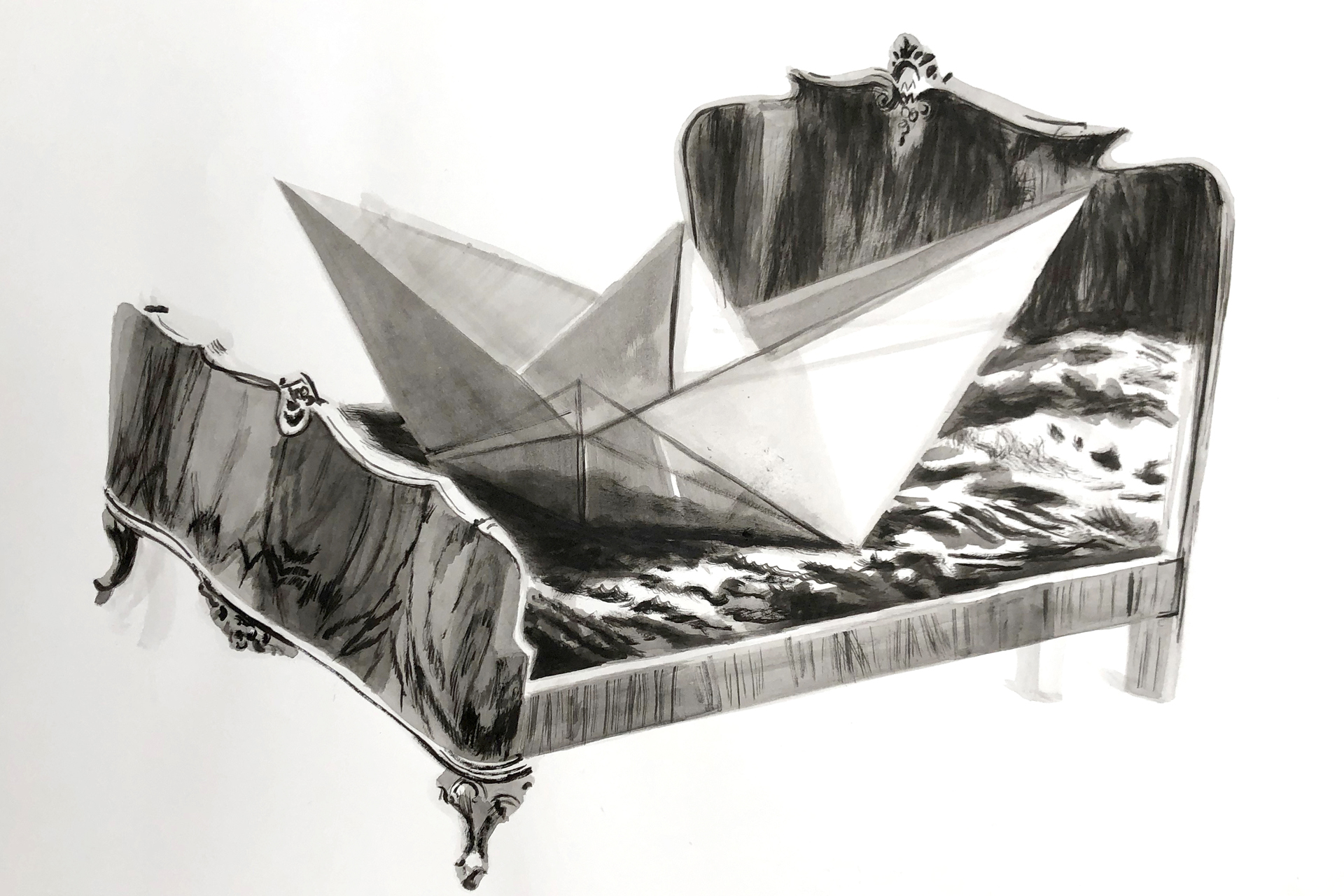

Illustration by Liana Zanfrisco, ink on paper, 41,5 x 30 cm, x2

2.

There is something wrong with the perspective from which people write about loneliness, even when stylistically there is nothing to criticise about such a text. Or rather, in the same way that the phrases of the loneliness argument are smoothly strung together, a deceptive image emerges.

However great the alienation and loneliness of the author who reports it, they have at least resulted in a text. In this sense the writer’s solitude was thus finite; words have now been found, and by means of those written words contact has been made with at least one other soul.

If such a text is valued and even becomes published, hasn’t this period of social isolation been a necessary starting point? Didn’t it ultimately lead to some form of success? Aren’t all these social hardships just the prerequisite for a glorious career as white-collar worker?

Olivia Laing’s widely acclaimed book, The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Lonely, tells of the loneliness of a series of New York artists, described from the perspective of an author who, for most of the period she lived in New York, was unhappy and lonely. She had come to the city to be with her boyfriend, but that relationship soon ended, and she lost the only bond that gave meaning to her move.

Laing writes long essays on artists such as Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, Valerie Solanas, and David Wojnarowicz. Their work is summarised and explained from the concept of ‘loneliness’ – which both plagued and marked all those artists. You could say that, in the best cases, they made their loneliness ‘productive’.

For example, The Lonely City offers a painstaking reading of Hopper’s best-known painting Nighthawks. If you look at that work closely for a long time, you can see that the illuminated ceiling of the diner has fine craquelure, that the paint has generally been applied very thinly and that the enormous shadow on the sidewalk contains a surprising amount of green; the sort of green so fitting for the night city, which you wander through alone in search of a companion.

In passing, Laing discusses the theorisation of loneliness, starting with the notes left by the deceased psychiatrist Frieda Fromm-Reichmann. She observes that loneliness literally leaves one speechless: the patient who suffers from loneliness cannot find words for the state in which she finds herself, while many psychologists, often out of an unconscious aversion to loneliness or fear of it, fail to ask the right questions, and tend to blame patients’ supposedly self-absorbed behaviour.

Ti vedo, ti sento by Liana Zanfrisco, ink on paper, 41,5 x 30 cm, 2019

Research has since shown that causality points in the opposite direction. Prolonged loneliness leads to a decreased ability to communicate, which in turn contributes to an individual’s social isolation, setting a downward spiral into motion.

Chronic loneliness is also detrimental to physical health. It leads to stress reactions, and as a result, hormones are produced that do not allow the body to relax. Sleep problems and irregularities in blood pressure often occur, ultimately contributing to a significantly lower life expectancy.

In The Lonely City, Laing tries to break through the silence on loneliness by also talking about her own experiences. Describing how one of Fromm-Reichmann’s patients remarked that hell is often depicted as a place where it is unbearably hot, while she herself experienced hell as a place where, isolated from the rest of the world, you live in a block of ice, lonely, Laing writes that she underlined those words (‘a block of ice’) with a ballpoint pen because, as she explains: ‘It often felt like I was surrounded by ice, or completely enclosed by glass, that I could freely see out but was unable to free myself or make the kind of contact I wanted to have.’

You could call this way of writing empathic. The author summarises the knowledge and discoveries of others and relates them to her own life. And when a writer does this repeatedly in a text, a literary technique is created. The technique of self-reference is ubiquitous in personal essay writing, especially as practiced in America. It is a precarious exercise, where you have to consider how much attention you pay to the topic under discussion and how much you pay to your own troubles. In an essay there isn’t anyone who upon reading a phrase like ‘I always have that now!’ can respond saying: ‘No, your issue is something completely different, and we’re not talking about you at the moment!’

Il suono del mare by Liana Zanfrisco, ink on paper, 41,5 x 30 cm, 2019

As Laing describes, David Wojnarowicz, who she consistently calls David, felt terribly alone as a teenager whenever he heard other kids calling each other ‘GAY!’ She remembers her own loneliness as a child. And while she emphasises that she herself did not experience the sort of violence that ‘David’ went through in his youth in New Jersey, she says she certainly does know what it’s like to feel unsafe as a child, how it feels to go through a chaotic childhood. It is apparently a moment of conciliation and confession: the writer talks about her own life and the insecurities and fears associated with belonging to a (sexual) minority – her own mother was a lesbian and came out late in life; the family had to flee the village, and her mother’s partner also had an alcohol problem.

David Wojnarowicz tackled his loneliness by having anonymous sex in the deserted harbour buildings on Manhattan’s docks. In the 70s and 80s of the last century (the decades before AIDS came on the scene), a crude and at the same time utopian community had arisen there where uninhibited (gay) sex was celebrated. Laing was inspired by this, she writes in general terms; she drew courage from the descriptions of Wojnarowicz’s wild sex life, and yet she is unable or unwilling to say to what extent she followed the example of his promiscuous existence.

These constant asides from the author will be perceived by many readers as intimate confidences; others, including myself, are more likely to feel beaten down by this constant self-reference, with the paradoxical outcome that in all those passages in the first person singular, I, as a reader, feel not so much engaged as excluded. Sometimes you also have that with people who talk too much about themselves, or talk only about themselves, usually in the victim role. The result is that – and Frieda Fromm-Reichmann warned about this – the person being spoken to even feels lonely.

La ragazza tra le nuvole by Liana Zanfrisco, ink on paper, 41,5 x 30 cm, 2017

3.

In my first years of study, I would camp out a week at my parents’ house every summer while my parents were on vacation. As a student I sought out the bourgeois luxury of my own home with a private garden. I had the opportunity to decide for myself what I did all day, there was not a single conversation I was obliged to have, I was free of roommates.

Reading meant looking into the minds of others, sharing in their observation skills, being intimate with lives that were alien to me. But it also meant acquiring knowledge, learning names, catching up. Reading is also a cerebral activity that excludes others.

The first days of those summer vacations I would read for hours on end, working my way through a stack of books half a metre high. In the afternoon I went for a run or a bike ride – after all, a healthy mind resides in a healthy body – and I managed to maintain this routine for days.

On the sixth or seventh day, however, I would invariably arrive at the point where I had had enough reading. No more information could be added. While I still had the energy to pick up a book, the letters no longer formed sentences, and a story emerging from the sentences was out of the question. The seconds ticked stoically by from the grandfather clock in the room, and I sat there all alone, cut off from the world. Suddenly, the energy to do anything was lacking; even masturbation was too much to ask.

I remember one particular afternoon when both I and my hunger for reading had become completely exhausted, so I decided to ride my bicycle to the forest where on many Sundays I had taken walks as a child. A parking lot, a forest path, and a large pit filled with sand. There was nothing going on at all, and yet I had once found this non-place the most adventurous spot on earth.

I passed by the parking lot, where two cars were parked, and a man and a woman were lying next to those cars; they had hardly any clothes on and were making love. The image shot by as if in a flash, but I had really seen it. Those two on the ground trying to become one with each other, and with whoever was watching them.

As I cycled home I kept laughing out loud, at the absurd situation, at the exhibitionist couple, and their helpless choreography in the grass full of forest ants, but just as much, and perhaps especially, at myself, the young man who locked himself up with a pile of books, supposing that they contained the entire world, a man who took pride in being so alone.

I was young. I was alive.

All'improvviso by Liana Zanfrisco, ink on paper, 41,5 x 30 cm, 2019

4.

People who are alone for a long time come to speak of themselves in the third person singular. This removes the boundary between the greatest objectivity and the greatest alienation.

There is a fundamental difference between romantic or artistic loneliness, that of the solitary soul, and the kind of loneliness that can never be put into perspective simply because it takes place at the end of a life. The loneliness of the elderly is a miserable run-up to death that no art can mitigate.

Death makes one lonely, that is well known.

In her book War’s Unwomanly Face, Svetlana Alexijevich writes: ‘Ask my husband instead, he enjoys talking about the past. He remembers everything, names of commanders and generals, division numbers. I don’t. I only remember what I experienced myself, my own war. You’re surrounded by people, but you’re always alone, you face death alone. I remember terrible loneliness.’

This essay was first published in October 2020 at de-lage-landen.comwith support from the Dutch Embassy in Brussels.