Loneliness and the art of being alone

By Marcelino Lopez

‘All our misery comes from the fact that we are incapable of being alone.’ Jean de la Bruyère (1645-1696), writer

‘Is there someone who you can phone when you’re lying in bed worrying about something?’ The answer to that question turned out to have predictive value for the likelihood a person will reach his or her 80th birthday. This has been shown by long-term happiness research from Harvard University. People who answered ‘no’ were unhealthier and died significantly earlier than those who said ‘yes’. Emotional connection is extremely important for our well-being. Just one person in your life can be enough to make a big difference.

Scientific research has linked loneliness to an increase in mental and physical problems. That is not surprising: humans were not designed to go through life as loners. It is estimated that about one in three adults feels lonely on a regular basis – one in ten even feels severely to very severely lonely. So if you consider yourself a member of the Lonely People’s Club, you are not alone.

How is it possible that, even though we share this planet with seven billion people, a large number of them still feel isolated? Especially in more prosperous regions, such as Western Europe. To better understand loneliness, we must first distinguish between being alone and feeling lonely. When you are lonely, that primarily says something about your state of mind, and only secondarily about your actual situation.

However you look at it, solitude is the foundation of our existence, something you can never run away from. Regardless of how many friends and loved ones you may have, you are forced to experience your life from a limited perspective. That’s just part of having a body. Only you know what it is like to be you now. And the same goes for me.

The only tool we have to come together from time to time is communication. But no matter how much we talk or do things together, after we say goodbye, we are both alone again. A happy human life requires a satisfying balance between being alone and being connected with others. And that balance is different for each person: there are hermits by choice who are blissfully happy and others who always need to be at the centre of attention and feel depressed and lost.

For this reason, loneliness is a more multi-faceted phenomenon than you would suspect at first glance. So it’s good to dive deeper into it. Loneliness may even be able to teach us a few vital lessons. In this article we look for answers to questions such as:

- What exactly is loneliness?

- How can loneliness be growing in a world where we are seemingly more connected than ever?

- What causes that emptiness in us?

- Why is it that it can hurt so much and shorten our lifespan?

- What are good and proven ways to deal with it?

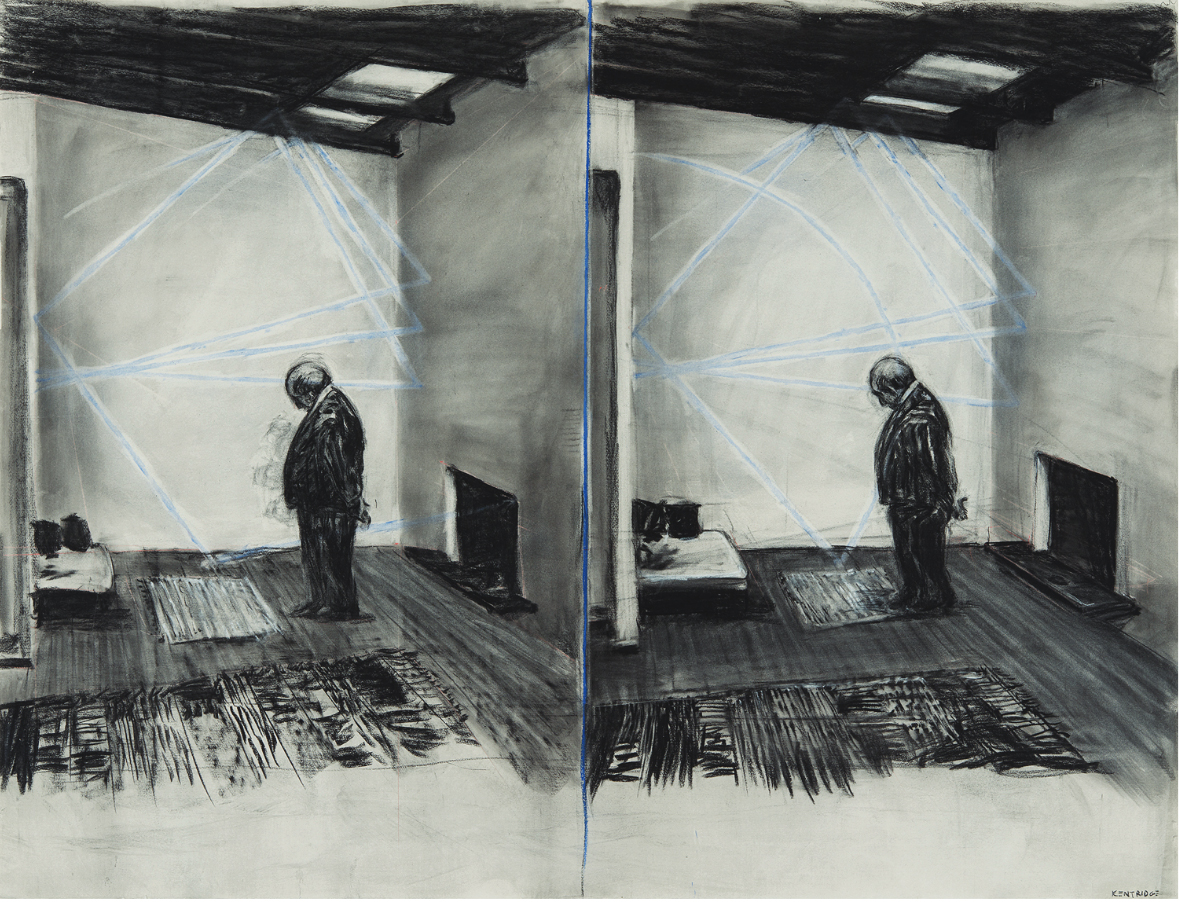

Stereoscope by William Kentridge, 1998-1999

Stereoscope by William Kentridge, 1998-1999Loneliness: inherited from evolution

People who suffer from it are sometimes ashamed of it, but the function of loneliness is very positive. Loneliness is nothing but the desire for connection (also called love or intimacy). And that desire is what makes you and me typically human. We are social animals, created to bind our fate to each other. The pain signals that you are missing this sense of belonging.

Like it or not, we have been ‘programmed’ by evolution to long for emotional security, intimacy, and acceptance by others, and to fear rejection and loneliness. If just one of your countless ancestors hadn’t been bothered by this – and had just leaned back their chair in a continuous state of bliss – you wouldn’t be here. Group acceptance was our ancestors’ most important life insurance policy. Back then, if you were expelled from the group, it more or less meant your death sentence, because it was impossible to survive on your own. That fact also explains why people throughout history believed the most bizarre things and participated in rituals that we would now consider insane. Belonging was much more important than doing your own thing.

To better understand emotions such as loneliness, it doesn’t hurt to look briefly at the instrument that causes them: your brain. Our brains have evolved over millions of years to help us survive, not to make us happy. Pain, fear, anger, jealousy, hunger: these are all signals from your body that tell you to do something to correct your situation. All our emotions (except for happiness) are Mother Nature’s ways to guide you safely through the complex (social) world. Your brain constantly scans your body and environment for ‘dangers’ and, if necessary, creates an urge to fill the most important gaps and avoid dangers.

A falling glucose level creates a feeling of hunger, so that you will make a trip to the fridge.

A low melatonin level makes you sleepy and makes you long for either a comfy sofa or a cup of coffee.

An oncoming car going a bit too fast creates an explosion of adrenaline in your body so that you immediately get the energy to jump away.

Loneliness makes you long for good company. Specific hormones and brain chemicals are involved here as well, such as oxytocin, serotonin, and endorphins (or a deficiency thereof).

The brain continuously creates the same cycles of emptiness, desire, action, and satisfaction using different hormones and brain chemicals. Sometimes that emptiness is literal, as in the case of an empty stomach, while sometimes it is metaphorical, as with loneliness.

Survival for humans is synonymous with ‘being able to work well together and form reliable relationships’. For this reason, many of our emotions are linked to how we manage our social lives. Jealousy, loneliness, fear of rejection, disappointment, falling in love, physical attraction, aversion: it’s all about relationships.

While our lives have changed dramatically since our ancestors roamed the forests in deer skins, our brains have not. The basic desires and fears are the same, which is why rejection and exclusion activate the same areas in the brain as when you fall off a bicycle. They cause real physical pain, and that’s exactly what people try to avoid.

Only psychopaths lack this. They see their fellow human beings mainly as instruments for self-gratification and lack this desire for a deep connection. The psychopath himself is the biggest victim of his own personality: he does not know real love. And that feeling – be it for a partner, child, pet, or friend – is what makes people happy and gives meaning to life. An intimate relationship or friendship is nothing less than a warm and safe home in an otherwise impersonal world.

Stereoscope by William Kentridge, 1998-1999

Stereoscope by William Kentridge, 1998-1999