A quest for imagined loneliness

By Nicole Montagne

During the months of the so-called smart lockdown, the media not only reported on the most dire consequences of COVID-19, they also wrote – since the containment applied to society as a whole – about less distressing issues. One of these issues revolved around the question of how we were all experiencing being (temporarily) cut off from each other. It won’t surprise anyone that an introverted person can deal with the altered circumstances better than someone who tends to be more of an extrovert. In fact, in some ways introverts thought it was just fine. Because, as we know, it’s precisely when he’s alone that this sort of person recharges his batteries. In contrast, an extrovert gets his energy from the hustle and bustle, from activities and action. Of course, the majority of people have neither completely one disposition nor the other.

Yet it was the extroverted people who indicated that they felt more lonely. And they appeared to take centre stage. Titia Ketelaar wrote on 20 May 2020 in NRC Handelsblad that the lockdown was being presented in extroverted terms. She quoted Prime Minister Rutte who said that ‘we’ had to ‘persevere’, and that we would only overcome the coronavirus ‘together’. She then referred to the Zoom socials, the phone calls, the emails, and the text messages with texts such as ‘How do you endure this?’. While for a large group of people (albeit still a minority) it wasn’t really a matter of ‘endurance’. Ketelaar also referred to the American author Susan Cain, who in her book Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking asserts that Western society is designed by and for extroverts. ‘Assertiveness is valued,’ said Cain. And what an assertive society requires is not so much identities as masks.

This is true. Modesty is no longer a virtue, and it is something that women (who appear to have more of it) need to unlearn instead of the other way around: teaching the indiscreet a bit of restraint. You have to be able to sell yourself. This can be done via social media, through your network (which is based not so much on friendship as on utility value), or by unabashedly pushing yourself to the fore. Think of the pitch of just a few minutes in which you’re allowed to bombard another person with a partial inventory of your belongings, your knowledge and skills, and your most impressive qualities. Whereupon that other person does not feel overwhelmed, but on the contrary, applauds. After which he or she may rattle off a similar pitch and receive the same kind of applause.

But this involves a curious twist. We ‘trade off’: I applaud you, and then you clap for me. We are on a sort of rollercoaster of extroverted enthusiasm and use superlatives (or hearts) for things that under normal conditions we would describe as ‘not bad’. But that very mask required in assertive society will ultimately lead to much greater feelings of loneliness. For when we constantly sell ourselves (or dole out unwarranted compliments) and engage in this sort of ‘trading’, we forget our unmarketable qualities, our ignorance and mediocre skills. We don’t sell everything. A considerable portion remains hidden.

Eskimo languages have many more root words for "snow" than the English language

Eskimo languages have many more root words for "snow" than the English languageLoneliness spread out

So, loneliness does not necessarily mean being literally closed off in a so-called lockdown. It’s more than that and may even concern something completely different. Such as what you’re not allowed to express or may even be incapable of expressing. With this impossibility in mind, I would like to examine the concept using a number of different images that attempt to describe it.

Voor Eenzaamheid (‘for loneliness’ in Dutch), an online platform by designers and artists that tries to develop a different view of loneliness, mentions a study by humanist counselor Lizette Schoenmaker. In 2013 she conducted research for the University of Humanistic Studies on the role loneliness plays in the process of becoming an adult. At the beginning of her study, she presents a discovery that I wish to limit myself to. Schoenmaker lists about 20 words that the Inuit use for snow. I had always been curious about what words the Inuit had for snow. What do they see that we, with our limited snow vocabulary, cannot?

However, in her translation of the Inuit words, Schoenmaker replaces the word snow with the word loneliness. In this way she wants to show how richly multi-faceted loneliness actually is. I will mention a number of these newly created, visual concepts. Nutagak: powder loneliness. Aput: loneliness spread out. Aniu: compressed loneliness. Ersertok: moving loneliness. Kimauguk: jamming loneliness. Massak: solitude mixed with water. Auksalak: melting loneliness. Ayak: loneliness on one’s clothes. Sillik: hard, crusty loneliness. Mauya: loneliness that can be broken through. Katiksunik: light loneliness that is deep enough to walk over. Iglupak: loneliness for making igloos.

You can picture each description. Loneliness on one’s clothes, now there’s an odd one. But I think I understand. A short conversation but no contact. Some of it lingers on, some of it remains, but it is actually nothing (and it quickly meltsaway). Or moving loneliness: it is not part of you, you can exist without it, and yet you are always bumping into it. Or loneliness spread out: wherever you go you let your lonely light shine. On people, objects, and things, on the sky, the earth, and the water, on the cutlery in the kitchen drawer, on your pillow and the setting or rising sun. There’s always that light. And just one more. Iglupak: loneliness for making igloos. I withdraw. Into my workplace, my studio, or behind my desk. I need to concentrate; I want to make something and don’t want to be distracted. I operate in silence.

Edward Hopper, South Carolina Morning, 1955, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper

Edward Hopper, South Carolina Morning, 1955, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York © Heirs of Josephine N. HopperHopper and Hammershøi

Schoenmakers has linked the expressive snow language of the Inuit to the concept of loneliness in order to visualise numerous variations of this concept. But of course, loneliness has also been visualised by artists, each in their own way.

Take Edward Hopper, for example. At first I wanted to bypass him, given that Hopper’s work has practically become an icon of loneliness to which little can be added. Nevertheless, his work can take on a slightly different meaning compared to other ‘artists of loneliness’.

The figures in Hopper’s paintings are usually alone. Alone in a restaurant, a café, a hotel room. Alone on a bed, behind a window, or in a hallway. And when they are not alone (less commonly), Hopper seems to have produced his paintings in the age of social distancing: his people are at an appropriate distance from each other. Alienation plays a role in his work and is even mentioned in some of his titles. But there is something else that stands out in his work, or in the type of loneliness depicted. It’s as if they’re seen through the lens of a camera. Hopper’s paintings are extremely cinematic. They could be movie stills. Or movie posters. They’re announcing something. Something occurred before this moment, and something’s about to happen. The still image suggests movement, a certain action, even if it’s hidden from your gaze. And as a viewer, you know: there is supposed to be an audience. The moment you look, you are that audience. But if you turn your gaze away, you still know that this image exists by grace of an audience. The lonely people on Hopper’s canvases need to be observed. Now, of course, you might think: Isn’t that always the case when you stand in front of a work of art?

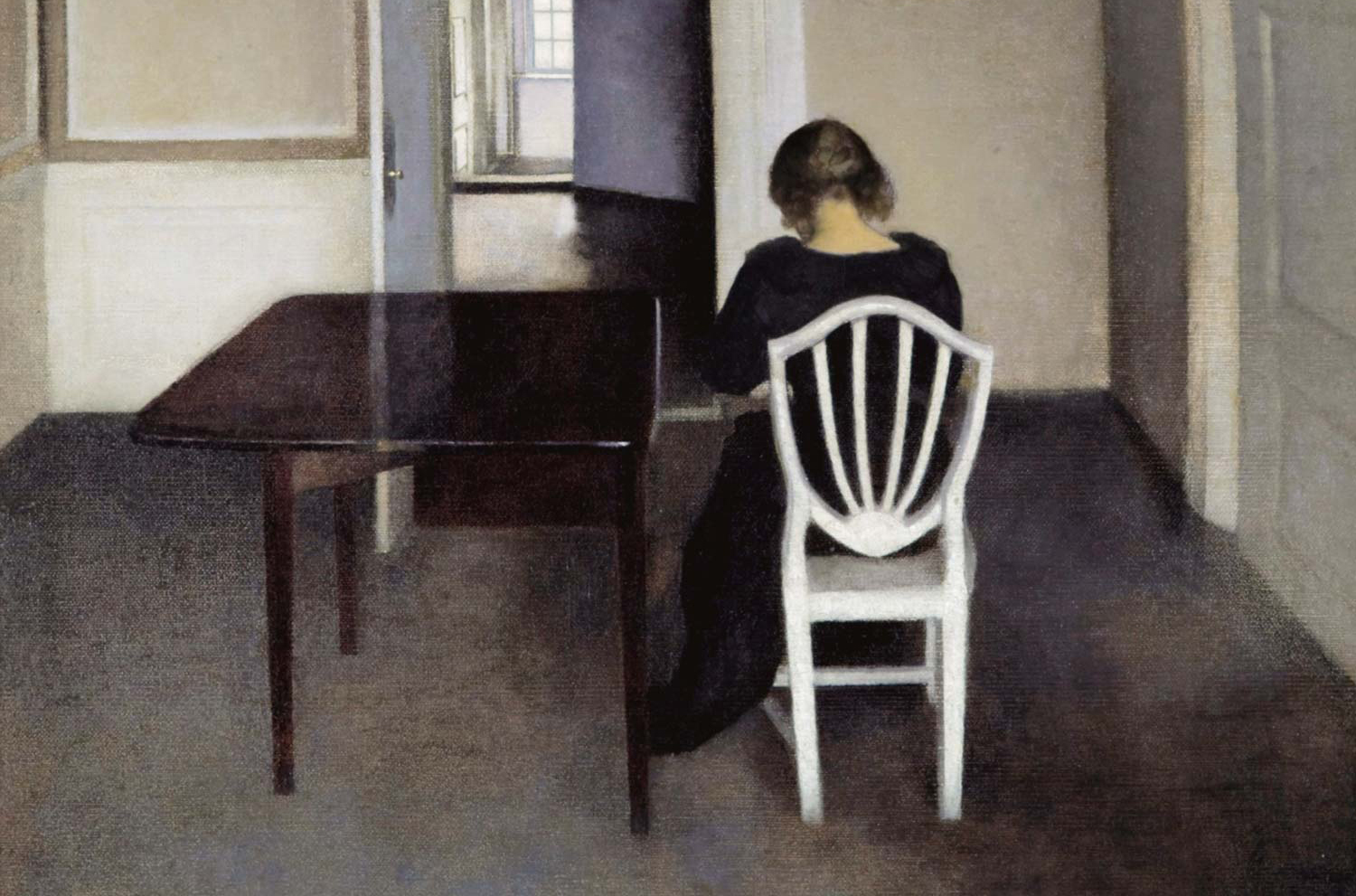

But no. Take the work of the Dane Vilhelm Hammershøi, also a painter of loneliness par excellence. Hammershøi’s work, unlike Hopper’s, retreats. Instead of bright, pronounced colours, here we find an array of shades of grey. Hammershøi must have had at least as many words for grey in his possession (or on his palette) as the Inuit possessed for snow. The work of this artist is subdued and does not necessarily call for the gaze of the outsider. His lonely figures, usually women, stand in a room with their backs to us. They seek no contact. They try to blend into that grey and are immersed in their activities. These women are at peace with their solitude. They are not usually in a room that is completely closed off. There is typically an open door leading to another grey room, or there is a window that offers a view of an outside world drowned in silence.

What about Hammershøi himself? He’s painted himself completely out of the picture. It is as if he was only invisibly present in that room, wary of disturbing the woman who is deep in thought. He wanted her to go on living without his gaze, and thus also without our own gaze. We look from the perspective that we’re not looking, that we’re not really there. That is entirely illusory, of course, but illusion is part of painting’s very nature. Hammershøi has depicted figures who feel unobserved in their solitude, and that must not be broken. Right at the point where Hopper shouts: Look! Look at that!

Vertigo by Leon Spillaer, 1908

Vertigo by Leon Spillaer, 1908Spilliaert and Schikaneder

Léon Spilliaert has taken yet a completely different approach. In his work, he has explored loneliness in relation to space. I will take De duizeling (The dizzy spell) as an example. This painting is also in shades of grey, and Spilliaert’s use of colour is also muted, just like that of Hammershøi. In De duizeling a woman descends a staircase with round steps. We see part of the staircase and view her from the vantage point of just below the woman’s feet. We see the small, safe part that she has travelled (shortened steps, because they are at the top and further away), we see the step on which she now stands (it is already becoming a bit more dangerous, because she now has to take a big step to move on from the step in question), and we also see that she still has a rather gruesome way to go: the exaggerated perspective not only makes the steps below her appear deeper (she will likely fall), but also steeper (she will certainly fall). And what will happen if she does fall? Because everything in the painting is cut off (the beach, the sea, the stairs, the woman’s shadow, her scarf flapping in the wind), everything seems to go on indefinitely. That infinity is further enhanced by the round steps, which suggest a loop. So the woman will fall and perpetually continue to fall.

It fills you with fear. Weren’t those our childhood fears: falling off the world and never getting anywhere? We could not even imagine the absolute loneliness of such a fall in an infinite universe. But we did feel that loneliness. Spilliaert gives spatial form to loneliness. Not only in De duizeling, but also in his other works. He always suggests endless progress, but strangely enough, that eventually reverses: he becomes claustrophobic. The artist constantly cuts off his images. Spilliaert thus depicts a paradoxical loneliness, one that is both claustrophobic and expansive. A spatial vision that exists merely in one’s head.

A Street in Winter by Jakub Schikaneder, 1905-1910

A Street in Winter by Jakub Schikaneder, 1905-1910And this is in stark contrast to the Czech painter Jakub Schikaneder, who depicted a much softer loneliness. Schikaneder is a so-called nocturnal painter. He painted at dusk, in the mist, or at night. Just look at Na Ztracené vartě (At the lost place). A coachman, huddled on the coach-box, drives his carriage down a snow-covered, bumpy road. On the side of the road is a house, shrouded in evening fog. It may be an inn. A warm light pierces through the window. Ahead, but not at the end of the road – because the end is receding – hangs a setting sun, whose light is subdued by the mist. Only the snow lights up. A couple of thin tree trunks that are almost black shiver in that cold white. But the sun calls out, as does the lighted window. In another painting, Ulice v zimě (Street in winter), it is night. We see an old wall. Ochre, lilac, grey. A lantern casts its light along the wall, partially revealing its own shadow. Snow here as well. On the pavement, on the road, on the roofs. The remains of a Virginia creeper, once fiery red, now muted, climbs the wall. In the wall a door, oval at the top. Next to the door a name plate, a plaque, but illegible of course. Behind the wall a part of a house, adjacent to another house, along which the street gently curves. At the top of the street another house, behind it a dome emerges, deep blue like the night. And down that street in that old Prague, along that wall and those isolated houses, walks a woman. We see her from a bird’s eye view, her head is slightly bent down. She is deep in thought. The night and the filtered glow of the lantern seem to stimulate her thoughts. But as a viewer, we have no idea what is going through her mind. Each time, Schikander slides the night, or the mist, between the person depicted and himself, or between the person depicted and the viewer. We human beings are separated by fog. And that too makes us lonely. Yet it is a soft loneliness, just as Hammershøi’s is soft; unless you’re clearly an extrovert, you would love to spend some time there.

Imagined lonelinesses. Hopper aimed a camera at the isolation, put it on the highest setting. Hammershøi painted himself out of the picture, letting his characters sink into the silence alone. Spilliaert placed the human being on an endless plane and instructed him to solve it on his own. And now walk! And now descend! Man has been thrown into his existence, but at the same time has been cut off. An existential loneliness. And then finally Schikaneder. Schikaneder loved his subject, even though he couldn’t come near it. He even liked the night and the fog and the mist, which all obscured his view of his beloved subject. Or made it acceptable. Because it had been rendered less hard and cold and fierce.

L’inconnu de la Seine, plaster mask of a drowned girl, around 1900

L’inconnu de la Seine, plaster mask of a drowned girl, around 1900Light in the distance

Images can reveal aspects of loneliness. Schoenmaker’s composite visual concepts did that. Paintings can do that. And now I want to turn to one final ‘kind’ of image that refers to that. An image that has not been deliberately designed. I am referring to the mask of the girl who went down in history as L’inconnue de la Seine.

Around 1900 the body of a 16-year-old girl was found in the Seine. Her body showed no signs of violence, so the girl was assumed to have committed suicide. No one came to identify her. And for that reason it will remain forever unknown who she was. The story goes that a young pathologist was so impressed by the girl with her serene smile (quite reminiscent of the Mona Lisa) that he made a plaster mask of her face. And many copies have been made of this mask. The girl — or rather, her mask with the blank expression — aroused the imaginations of writers and artists. Nabokov, Rilke, Döblin, Camus, Blanchot, and many others have written about her. Greta Garbo is said to have even modelled her physical appearance on this stranger. Over time, the girl’s mask became an icon.

i c o n by Frederik Neyrinck, Sabryna Pierre & Atelier Bildraum

i c o n by Frederik Neyrinck, Sabryna Pierre & Atelier BildraumI c o n is also the name of a musical performance, directed by the artistic duo Bildraum, which premiered in 2018 and is based on the cult around L’inconnue de la Seine. The exhibition transports the girl’s mask to the present and examines what meaning this mask (this ‘mythical selfie’) can still have in our time, a time in which we are overwhelmed with images. Bildraum wonders why we always project our desires and our deficiencies onto selfies, or onto masks and icons.

You can project anything onto a mask (a selfie, an icon), of course. The sad thing is that in no way do we approach the essence of the (self-)drowned girl. Not only because she is dead, but chiefly because we don’t know who she was, and therefore cannot do her justice posthumously. Just imagine: her plaster effigy adorns I don’t know how many rooms as a cult object (it appears to still be available for sale), many eyes gaze upon her every day, and yet she is observed without being seen. You could say that this is lonely. Indeed, what we discover in her image is our own deficiencies and desires, not hers.

But why do we always want to fill in mystery with identity? And how much room do we leave for white space, Bildraum wonders. That is an interesting question. Especially now that we know how many nuances a white space can have. Perhaps we can do more justice to the girl’s loneliness if we don’t fill her in but draw a circle around her in a nuanced way, in the same way the Inuit approach snow. After all, loneliness by its very nature cannot be put into words or directly depicted. If it could, she would no longer be lonely. The unsaid and undepicted constitute her essence. So, loneliness is enigmatic. And we will all have perceived this in that girl: if we look at her serene image, we are beholding a secret. And we also see a certain mystery in the work of Hopper, Hammershøi, Spilliaert, and Schikaneder. It is out of our reach, but we understand that it’s out of our reach. Perhaps this realisation is even a mild antidote to loneliness. Maybe we can make others, or ourselves, a bit less lonely by accepting that inaccessibility. Because something is certainly there that is unreachable or ineffable. Otherwise it would be non-existent.

He who is lonely experiences that which is inaccessible as a beckoning light in the distance. It calls out to us and moves out of the way, it always dances exactly on the extremely thin line of the horizon, or it lies at the bottom of that nearly endless staircase, but it is there; we know about it. Even though you can never put your hand on it.

This essay was first published in October 2020 at with support from the Dutch Embassy in Brussels.